Reverse resolving a public IP - no problem here

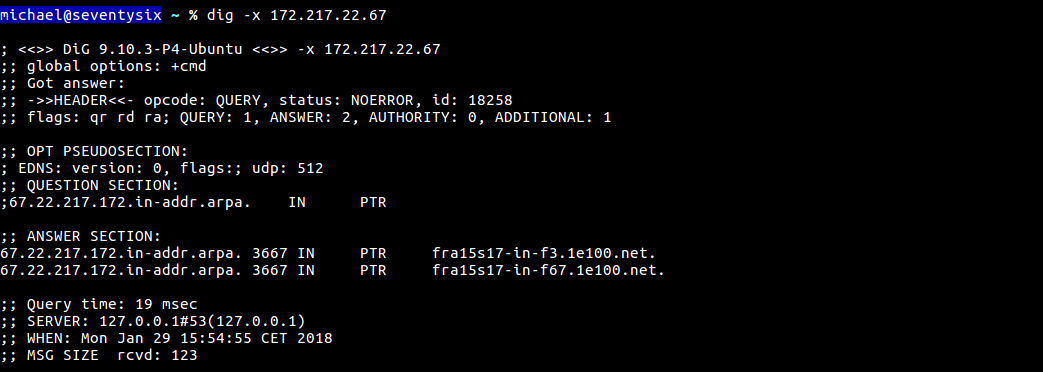

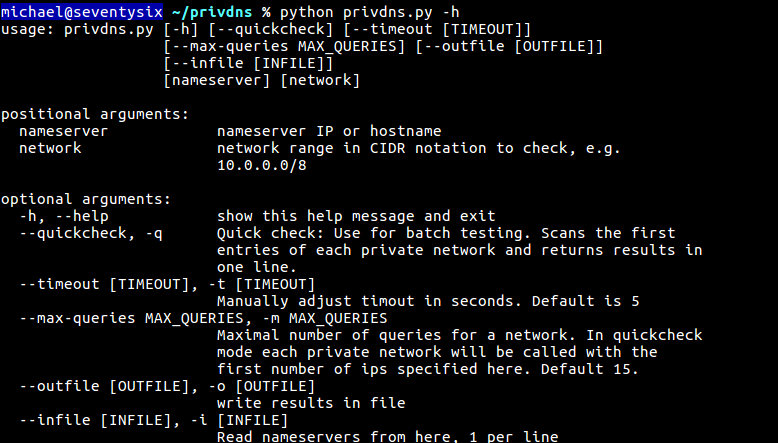

Tl;dr: A few nameservers might expose internal IP addresses and domain names when directly queried to reverse resolve private IPs. Check with dig -x or have a look at privdns.py.

A simple mistake

I recently made a small and seemingly unimportant mistake: I tried to contact a server from a company’s infrastructure but was not logged in to their VPN. Boring, you may think, happens every day. But a few hours later I was writing python code and mass-scanning the internet for DNS servers. And even though I wasn’t _that_successful in the end (which is good from a security perspective), it was still a fun experiment. Here is what happened.

When I tried to ping the internal company server, I got the following response:

michael@seventysix:~ ping internal-db1.example.com

PING internal-db1.example.com (10.0.0.1) 56(84) bytes of data.

^C

--- internal-db1.example.com ping statistics ---

3 packets transmitted, 0 received, 100% packet loss, time 2014ms

Of course, a timeout. But notice something: The domain name resolved. Even if I was not logged in to the VPN, I still could resolve the internal domain name. To make sure this was not due to some DNS cache, I tried to reproduce this from a VM in the cloud that had never been logged in to the company network and used a different nameserver - and got the same result.

To understand, why this is interesting, here a little background on IP addresses and DNS.

Internal, external IPs and DNS

IPv4 and IPv6 address spaces are divided into private and public IPs. The following networks are private:

- 10.0.0.0/8

- 172.16.0.0/12

- 192.168.0.0/16

- fc00::/7

Private IPs are used, for example, in your home network or in internal company networks. If you are dealing with company servers in an internal network, they usually have IPs from the above ranges.

For connecting names and IP adresses, we use DNS, the domain name service. DNS servers (or “nameservers”) are servers whose purpose it is to translate domain names like example.com to an IP. Old news, so far, you probabaly knew that. The same thing is used in internal company networks: Instead of having to remember 10.0.0.1 as the IP of the internal database server, they also use a DNS to translate domain names like internal-db1.example.com to a private IP, e.g. 10.0.0.1. So when your average Windows desktop client tries to connect to the database server, it asks the DNS server to resolve the domain name internal-db1.example.com to an IP which it then can talk to. (If you want to know more about DNS I encourage you to watch this nice, concise video from the great internets - and no, that’s not me:)

In some companies, the same DNS server that manages domain names for internal IPs also manages domain names for their public IPs, e.g. the domain for their website. The request “Who is www.example.com” and “Who is internal-db1.example.com”, can be answered from the same DNS server - the company’s DNS server ns1.example.com. This is what had happened in my case where ns1.example.com was set up to resolve internal and external IPs. It just didn’t care if the requests to resolve the internal IPs came from the inside or outside of the company’s network and so it replied to my request

=> "Who is internal-db1.example.com"?

with

<= "Hey, it's 10.0.0.1",

not bothering that it was responding with an internal address to an DNS request from outside of the company network.

Another requirement that was needed to make this incident possible was that the company used the same domain name for internal and external services. Their website was named

www.example.com.

The internal database server was named

internal-db1.example.com.

When pinging internal-db1.example.com, I wasn’t explicitly querying the comapny’s DNS, since my home DNS is set up to use a different DNS (let’s say it was Google’s DNS). As DNS has a distributed structure, if Google’s DNS wants to get the IP for www.example.com, it first asks one of the root DNS servers that are responsible to keep track of who is responsible for second level domains like example.com. The contacted root server replies to Google’s DNS with the IP of ns1.example.com as authoritative nameserver for the domain example.com. Then Google’s DNS asks ns1.example.com to resolve internal-db1.example.com and receives the answer it finally forwards to us - the internal IP we have seen above. Had the internal domain name been internal-db1.example.local, Google’s DNS would not have known who to ask for that top level domain (.local), since the company that registered example.com is not registered (and couldn’t be) for example.local.

Think about it: At this point, Google’s DNS knows the company’s internal domain name and corresponding IP. And every other DNS server on the internet that was queried for internal-db1.example.com would get to know the same thing. Not a big deal at first glance, but as someone trying to protect that infrastructure I hope you still find that at little scary.

A small information leak

Apparently I now could resolve internal domain names of the company from outside of their infrastructure by just asking any public DNS. What makes things a little more interesting is that many companies use to enumerate servers:

- db1-internal.company.com

- db2-internal.company.com

- db3-internal.company.com

etc. - meaning if you know one server name, you can guess the others. Of yourse, you can also try to bruteforce domain names, maybe dev-internal.company.com or log-internal.company.com actually exit. The info leak here is that you can bruteforce internal domain names and check if machines with those names exist in the company network, retrieving interal IPs without being logged in to the network. But you still have to bruteforce domain names. (Yes, there are tools to do that.)

A bigger information leak

If you do know a bit about networking, IPs and DNS, you probably guess what my next step was. Many people know basically how DNS works. What less people know is that you cannot only resolve a domain name to an IP address, but also go the other way round: Given an IP address, you can resolve it to a domain name. This is called reverse resolving, or reverse DNS, in contrast to forward DNS, and it is done by querying the DNS for PTR-records of special ARPA-Domains. If you want to reverse resolve a given IP, you literaly have to reverse the IP address and add a special domain to it, the in-addr.arpa.net domain. E.g. for revere resolving the IP 1.2.3.4you ask your name server to look for an entry for

4.3.2.1.in-addr.arpa.net

of type PTR (in comparison to type A for IPv4 or AAAA for IPv6 addresses when forward resolving domain names).

When you “own” an IP like 1.2.3.4 (which means it is registered for you at IANA) you can specify an authoritative nameserver for the corresponding domain 4.3.2.1.in-addr.arpa.net and configure a PTR entry specifying a domain name on that nameserver. If anyone tries to reverse resolve 1.2.3.4 she gets redirected to your nameserver and looks for the PTR entry. (You can only attach one domain name to an IP address, even if multiple domains are attached to the same server.)

So back to the company example.com. If I could not only get an IP address for a domain name, but also the other way round, was there some way to check if an internal IP address had a domain name associated to it? Could I just do reverse queries for private IP spaces? That would make things way more interesting. If that was possible, I could simply start iterating through the private IP spaces, check for each IP if there is a PTR record registered to it, and in this way get a lot of information about the internal company network - IP addresses, domain names, and all infos I could derive from these.

Due to the structure of DNS, simply reverse resolving IPs did not work: Reverse resolving meant quering your default nameserver (e.g. Google) for an internal IP like 1.0.0.10.in-addr.arpa.net. Since nobody can own that IP and specify her nameserver as authoritative, the IANA doesn’t allow you to place an entry here and as result, Google’s DNS would not be able to handle a reverse DNS query for this IP, as it had nothing to do with company.com. It would not, as in the case of domain resolving, try to contact our company’s DNS, because it had no clue that our company’s DNS would see itself as authoritative for this internal IP.

But - what would happen if I tried to contact the company’s nameserver directly and ask if it kindly could resolve 1.0.0.10.in-addr.arpa.net for me? No Google DNS in between that wouldn’t know what to do. And though it really wouldn’t make sense, not being able to register private IPs with the IANA would not prevent a DNS admin to configure reverse resolution at his nameserver, would it?

The company’s nameserver did not disappoint:

michael@seventysix:~ dig -x 10.0.0.1 @ns1.example.com

; <<>> DiG 9.10.3-P4-Ubuntu <<>> -x 10.0.0.1 @ns1.example.com

;; global options: +cmd

;; Got answer:

;; ->>HEADER<<- opcode: QUERY, status: NOERROR, id: 6077

;; flags: qr aa rd; QUERY: 1, ANSWER: 1, AUTHORITY: 0, ADDITIONAL: 1

;; WARNING: recursion requested but not available

;; OPT PSEUDOSECTION:

; EDNS: version: 0, flags:; udp: 4096

;; QUESTION SECTION:

;1.0.0.10.in-addr.arpa. IN PTR

;; ANSWER SECTION:

1.0.0.10.in-addr.arpa. 3600 IN PTR internal-db1.example.com.

;; Query time: 16 msec

;; SERVER: XXX.XXX.XXX.XXX#53(XXX.XXX.XXX.XXX)

;; WHEN: Wed Jan 21 14:37:49 CET 2018

;; MSG SIZE rcvd: 110

You see that beautiful “ANSWER” section? That’s it. We reverse resolved the internal IP with the help our company’s nameserver. This is when things got really interesting, because nothing would stop me from iterating through the whole private IPv4 adress space to reverse resolve each IP of the company’s network with the help of their external reachable DNS server from outside of their network. Pure fun.

Automate all the things

All I now needed was a script to iterate through the private IP address space to get all the internal domain names and IP addresses from that company. A nice and simple information leak due to a misconfigured DNS. (Later I was told that the DNS wasn’t actually “misconfigured” but that this was totally on purpose to overcome some VPN DNS resolution problems. To really get that kind of reverse IP address resolution, you usually need to set up an appropriate zonefile which means you must configure it explicitly to reverse resolve internal IPs. Anyway, at least the reverse resolving part had been fixed silently a few hours later.)

After having found the flaw, I was also curious to see how common it was and how many DNS admins had applied a similar configuration. I wrote a python script to reverse-query the first 15 hosts of each private network range for a given nameserver and started scanning the internet for domain name servers. After some trouble with masscan (- which worked fine, in the end), I downloaded a list from Shodan with around 20.000 DNS servers and checked them over the weekend. The results weren’t spectacular, but some interesting hits where there. I informed some of the affected the companies, but also found private routers (mostly Broadcom) that revealed names like “Michael’s iPhone” or HP printers, Amazon sticks and stuff like that.

michael@seventysix ~/privdns % ./privdns.py XXX.XXX.XXX.XXX 10.0.0.0/8

[*] Checking nameserver XXX.XXX.XXX.XXX

[+] 10.0.0.1 : E***.net.

[+] 10.0.0.2 : P***.net.

[+] 10.0.0.3 : A***.net.

[+] 10.0.0.4 : A***.net.

[+] 10.0.0.5 : E***.net.

[+] 10.0.0.6 : E***.net.

[+] 10.0.0.7 : P***.net.

[+] 10.0.0.8 : P***.net.

[+] 10.0.0.9 : E***.net.

[+] 10.0.0.10 : P***.net.

[+] 10.0.0.11 : a***.net.

[.] Resolved but no entry for 10.0.0.12

...

You find the script on my GitHub if you want to play with it yourself. After all, it’s just an information leak and from what I have seen not too common. As far as I know, it also requires a rather specific DNS configuration.

And that’s it. That’s the story of how reverse resolving private IPs on a company’s DNS leaked their infrastructure domains and IPs - and no sophisticated hack or exploit was necessary.

For comments, questions, critique etc. contact me on Twitter.